Our Stories

Recent Articles

History & Discoveries

Peeking Through the Draperies of National Statuary Hall

A short history of this significant space's special fabric.

History & Discoveries

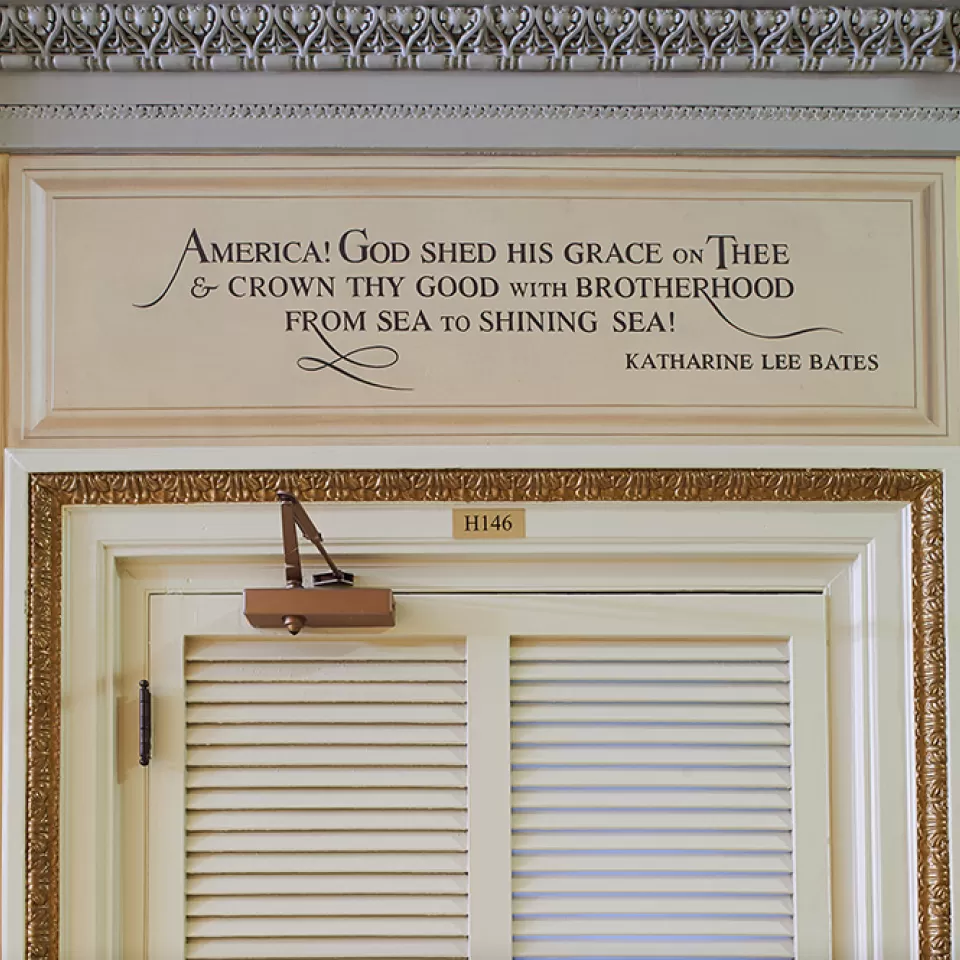

Capitol Lyrics: "America the Beautiful"

The lyrics of this patriotic song are found easily at the U.S. Capitol.

History & Discoveries

A Hallowed Figure in American Art and Culture: the Bald Eagle

The bald eagle is painted, sculpted and carved throughout the Capitol campus. Its white head, wide wingspan and gnarled talons are ubiquitous.

History & Discoveries

Unearthing Capitol Hill's Buried History

Visit Congressional Cemetery and discover the many connections the Architect of the Capitol has to this hallowed ground.

Add new comment