Our Stories

Recent Articles

Behind the Scenes

Tools of the Trade: Sheet Metal

The AOC's Capitol Building Sheet Metal Shop craftspeople utilize traditional, handheld tools alongside current technologies to shape, fit and repair metalworks.

Behind the Scenes

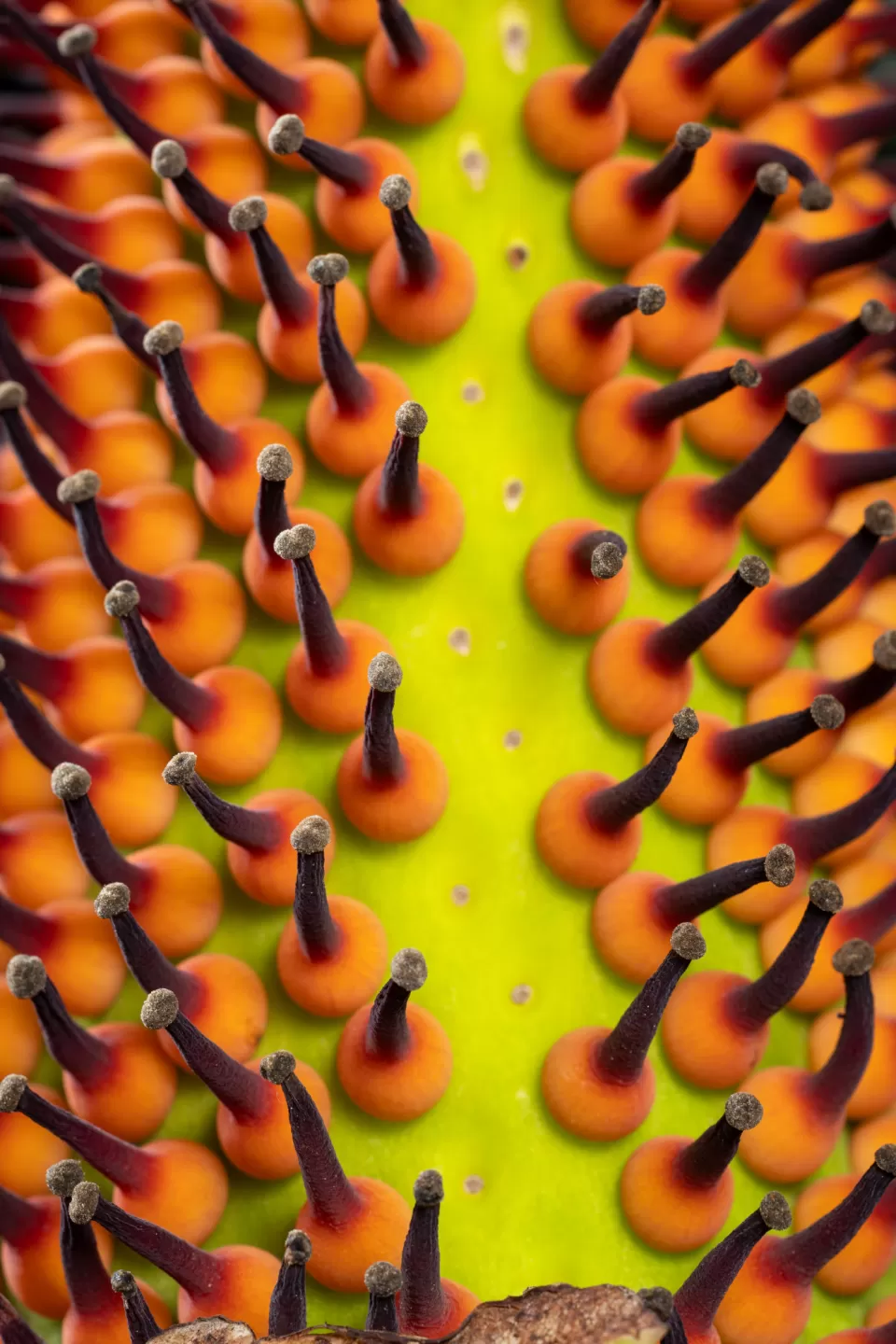

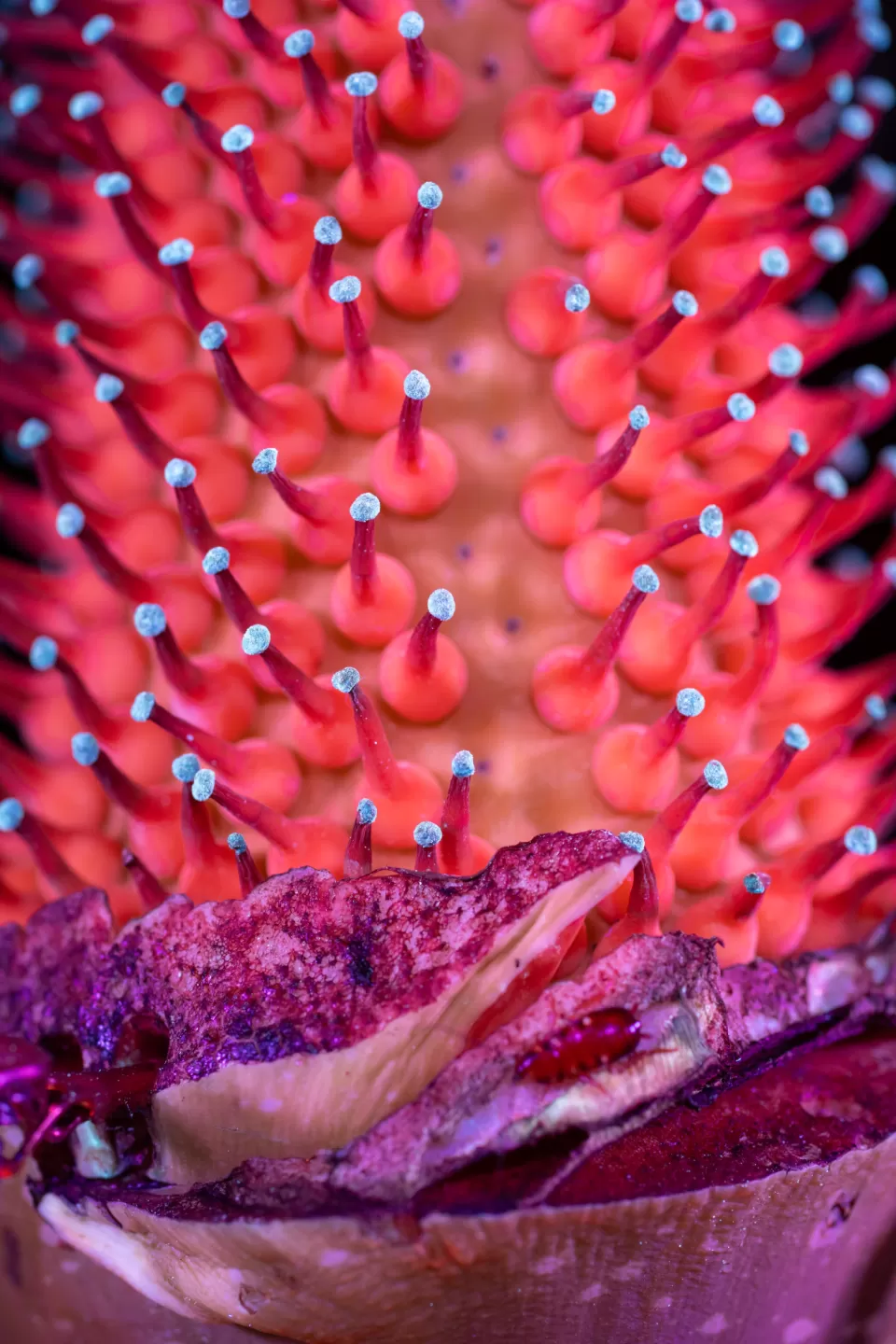

The People's Gardens

Take a stroll through our pictorial tour to experience the beauty of these unique garden beds and meet a few members of the jurisdiction's Gardening team that work hard year-round to keep the Capitol campus looking beautiful.

Behind the Scenes

Hanami on the Hill: Cherry Blossom Season on U.S. Capitol Grounds

Nestled on the grounds of the U.S. Capitol, these trees stand as a symbol of renewal and spring. A few of the oldest recently received some unique preservation care.

Behind the Scenes

Picture Perfect: Capturing Iconic Images of the U.S. Capitol Grounds

See the Capitol campus through the eyes of an AOC Photographer.

Add new comment